Ashifi Gogo '05

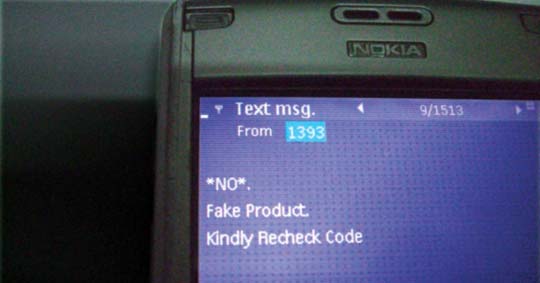

After consumers send a cell phone text message with the numeric code listed on the drug, they receive a text message identifying the product as fake (as shown) or authentic.

When patients go to a drugstore to pick up medicine, they expect it to be authentic and to manage or resolve a health condition.

But what if that prescription was fake, a counterfeit drug that could cost them their health, or even their life? That is a critical concern for many patients outside of the United States, said Ashifi Gogo ’05, a graduate engineering student at Dartmouth College. He is co-founder of mPedigree, a nonprofit organization working to protect the prescription drug supply chain in West Africa through cell phone technology he helped develop.

The World Health Organization calls counterfeit medicines “an enormous public health challenge.” Counterfeit drug sales are projected to reach $75 billion globally by 2010, an increase of more than 90 percent from 2005.

The World Health Organization calls counterfeit medicines “an enormous public health challenge.” Counterfeit drug sales are projected to reach $75 billion globally by 2010, an increase of more than 90 percent from 2005.

“Some of the counterfeit medicines don’t contain anything; it might be cornstarch pressed into a pill,” Gogo said. “Other medicines may contain too much or not enough of an active ingredient.” The worst-case scenario is a counterfeit that contains deadly toxins.

Gogo is particularly concerned with counterfeit malaria pills in his native Ghana. “People take an anti-malaria pill thinking it’s effective, so when they get malaria, they typically don’t go to the hospital,” he said. “By the time they seek treatment, they are in the later stages of the illness.” He knows this from experience. After contracting a regular case of malaria, he took the predominant anti-malarial medication that was authentic but slowly being replaced due to reduced efficacy. The result was an unsettling midnight hospital visit. “I experienced what it would be like to take a fake drug,” he said. “I could have been a Ph.D. candidate killed by a disease that has flu-like symptoms and is easily curable with over-the-counter medication.”

— Ashifi Gogo ’05

Existing technology can help identify counterfeit drugs, but all the “techno-centric” methods tend to be either too high-tech for a developing nation — Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) tags and nanoparticle embedding, for example — or provide too little protection, Gogo said.

The identification method developed by Gogo and his classmate from Ghana is simple, cheap to implement and effective. Gogo explained it like this: “Lottery ticket-type numeric codes are placed on the drug’s packaging. When you buy the drug, you scratch the panel and see a string of 13 digits. In Ghana, it’s very simple. You just send a free cell phone text message with the information to a four-digit number — 1393, very easy to remember. You get an instant response to indicate if the drug is genuine or fake while you are at the pharmacy. If the drug is fake, you can query the pharmacist and keep testing drugs until you get an authentic medication or take the matter up with law enforcement agencies, armed with factual evidence of counterfeit medication.” This method is viable because cell phones are plentiful in Ghana, he noted.

A trial run of mPedigree’s authentication method in that country in the first quarter of the year was successful, and the project will be launched with local drug manufacturers this winter.

Ashifi Gogo ’05

“Next,” said Gogo, “the project needs to migrate to Nigeria. Studies show Nigeria has a pressing need for anti-counterfeit solutions — when INTERPOL did a drug audit in Lagos, Africa’s most populous city, four out of five pharmaceuticals were fake. That’s 80 percent of the drugs, only five years ago,” he said. “How do you survive in such an ecosystem?”

While mPedigree implements this technology, it also works to amend laws. “We’ve had initial success,” Gogo said. “The Ghanaian law enforcement agency created a special unit for counterfeit issues and is working on moving counterfeit activities to the same punitive level as narcotics,” he said. “Just a few months ago, the Ghanaian FDA organized the nation’s first anti-counterfeit conference, inviting notable West African health experts, such as Professor Dora Akunyili, who survived an assassination attempt linked to her efforts to rid Nigeria of fake drugs.

“It’s a start, but there’s much more to do,” Gogo said. “Experts indicate that the large fake drug operations are being run by former narcotics drug rings, mainly because of the comparatively lenient punitive measures for fake drug operations in many developing nations.”

As Gogo travels back and forth between African countries, personal security is paramount. However, the risk hasn’t slowed him down. He continues his work with legitimate drug manufacturers in Africa and his studies at Dartmouth. Through the engineering school’s Innovation Program, Gogo receives entrepreneurial training and the theoretical and technical expertise he needs to keep his drug authentication initiative moving forward.

Gogo double-majored in math and physics and minored in economics at Whitman, where he was, admittedly, “all about the academics.” That academic rigor included opportunities to tutor other students in math and physics, “a positive, rewarding experience,” co-author a paper published in the “Physical Review,” present a paper at a physics conference in Victoria, B.C., and participate in professors’ research, including that of Associate Professor of Physics Mark Beck, who worked with Gogo on an experiment to demonstrate a “Quantum Eraser.”

Beck describes Gogo as a “very good student who worked hard. He was especially adept at computer programming, and it seems that the technical side of the business he started requires that skill.”

“I wanted to find a career that would help me get home (to Ghana) for the long term,” Gogo said. “I switched to engineering when applying to grad schools because I could work with my hands and produce something useful for developing nations.”

That something, it appears, is helping to secure the pharmaceutical supply chain of West Africa.

— Lana Brown

Editor’s note: To listen to a recent BBC World Service radio interview with Ashifi Gogo, visit the mPedigree Web site.